- Home

- A. L. Sirois

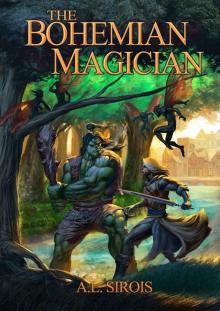

The Bohemian Magician

The Bohemian Magician Read online

THE

BOHEMIAN MAGICIAN

By

A.L. Sirois

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this book are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Dragon Scale Publishing, 212 E Crossroads Blvd. #119, Saratoga Springs UT 84045

The Bohemian Magician

Text Copyright © 2017 by A.L. Sirois

Artwork Copyright © 2017 Dragon Scale Publishing

Published by Dragon Scale Publishing

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1943183548

ISBN-13: 978- 1943183548

Front cover art by Luciano Fleitas

To my wife, Grace Marcus, for her continued love, inspiration, and sense of humor.

Acknowledgements

I owe thanks to Chris Bauer, Kevin Breaux, Donna Galanti, Val Nieman, and John Shirley. Special thanks go to my editors, Rachel Ferguson and Sam Ferguson, whose endless patience helped shape this book into its present form. Any errors or infelicities are entirely my responsibility.

Other Books by Dragon Scale Publishing

Codex of Light, by E.P. Stein

The Protector of Esparia, by Lisa Wilson

The Dragons of Kendualdern: Ascension, by Sam Ferguson

The Lost City of Alfarin by Keaton James & Sam Ferguson

Kingdom of Denall Series by Eric Buffington

The Troven

Secrets at the Keep

The Changing

The Dragon’s Champion Series by Sam Ferguson

The Dragon’s Champion

The Warlock Senator

The Dragon’s Test

Erik and the Dragon

The Immortal Mystic

Return of the Dragon

The Haymaker Adventures by Sam Ferguson

Jonathan Haymaker

Brothers Haymaker

The Eye of Tanglewood Forest

Also available online exclusively on Dragon Scale’s blog:

Tharzule’s Tome of Wishes

Orcs and Elves

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

About the Author

Other Books by Dragon Scale Publishing

PROLOGUE

IN WHICH GUILHEM HAS A STRANGE ENCOUNTER

Twelve-year-old Guilhem, the duke’s son, threaded his way through the dark castle corridors. The servants had been awake for some hours though the sun was barely peeping over the horizon. Cooking odors from the great kitchen wafted along after him through the stone halls. He ducked and wove his way past servitors bearing food to his father, who was ill abed this past fortnight—very much unlike him. Guilhem knew the duke, his face gone hollow and pale, would do no more than pick at the food. He worried about his father’s health, but this morning he had scant room in his mind for sorrow or concern.

The watchman’s pipes, three notes played from the donjon’s turret to greet the new morning, had awakened Guilhem. Usually he would have squirmed deeper into the down coverlet for a bit more sleep, but today he was up and out of bed before he had time to notice the chill in the air. Yes, there was no mistaking that autumn was here. He dashed to the window, yanked back the drapes to see how the weather was. The riot of color staining the surrounding trees gladdened his heart, because it heralded the coming of the holiday season, while simultaneously giving him a twinge of regret for the passing of summer. Satisfied that the day would be clear without a chance of rain, Guilhem splashed some water on his face from the washbasin on the table beside his bed. Yanking his nightshirt off over his head he began pulling on his clothes, breeches and a long shirt with a tight-fitting leather pelisse over it, suitable for a chilly morning.

Outside in the drafty corridor his closest friend, Henri Dufour, awaited him, wrapped in a cloak, pacing back and forth to keep warm.

“How long have you been out here?” Guilhem asked.

“Too long, too long,” Henri grumbled. He was a slight, olive-skinned boy with dark eyes set in a narrow face, Guilhem’s best friend since earliest childhood. “Come on, Guilhem; it’s just after primes and we need to be back before tierces.” The boys fell into step, with the shorter Henri fairly skipping in his eagerness to be out of the castle.

But Guilhem refused to be hurried. He was only lately becoming aware of the need to maintain a certain dignity, because, as his father said, he was different from all the other boys. “So? That’s mid-morning, more two hours from now. Plenty of time.”

“So you say,” said Henri with a scowl. “You’re not likely to get a buffet on the ear from Brother Gabriel if we’re late. He’ll take it out on me. On me!” Both boys were having trouble getting back into the rhythm of daily lessons, only recently begun again after the languid summer. Along with other boys of noble blood, they were obliged to report to the small schoolroom off the chapel, there to labor at Latin, geography and history under the watchful eye of old Brother Gabriel, who had no compunctions about slapping anyone, even Guilhem the duke-to-be, for being tardy or lax in his studies.

“No, he won’t,” Guilhem said. “Not if we bring the fat old fellow a coney for his pot. He’ll go easy enough on us for that, I warrant.”

Henri grunted, but couldn’t argue the point. Brother Gabriel’s fondness for food and drink was well known. There wasn’t a one of their schoolmates who hadn’t brought the monk a rabbit or a partridge at some point in his academic career in the hope of receiving lenient treatment in the classroom. Brother Gabriel accepted all such gifts, referring to them as “remembrances,” but they seemed to have no effect on his propensity for meting out punishment.

Guilhem partook enthusiastically in horsemanship and arms training, but they were a relatively small part of his learning. He rode well despite being a bit small for his age, and was dexterous with the sword, mace and knife, and better than average with bow and arrow. When he attained his full growth, he knew he’d be a formidable fighter. To that end, he and Henri often sparred with blunt practice swords, perfecting their thrusts and parries. In the practice yard Henri’s innate skills with weapons gave him an edge on Guilhem, who was determined not to let himself be bested. More than once they had come out of their contests bleeding, but with no ire for each other.

As far as the rest of his education was concerned, Guilhem enjoyed music and poetry, but otherwise hadn’t much use for reading despite Brother Gabriel’s best efforts. Guilhem’s father, himself a learned man, owned a small library of which he was inordinately proud, and Guilhem knew it was his responsibility to be fully literate, so he applied himself to his Latin, assisted by a flair for languages that had already given him fluency not only in his native French, as spoken in his father’s court, but also the regional Occitan tongue used by the commoners.

Even so, he had more than once wished he had been gifted with Henri’s precise memory. The swarthy boy never forgot a thing.

What drew them together,

though, was a shared passion for falconry and hunting. Having received their own birds to care for in the past year, they spent as much time as possible training their charges to hunt.

And sometimes that meant braving the chill of an early morning.

The boys stopped briefly in the kitchen where the day’s loaves were already baking, and wolfed a quick breakfast of oranges, yesterday’s bread, and a cup of wine. Then they ran down to the kennels. Some of the dogs still lounged around in the piles of straw that were changed daily, scratching themselves and yawning; but others, seeing Guilhem and Henri arrive, scrambled to their feet and sat expectantly by the gate with tails wagging. They knew the boys’ presence at this hour meant only one thing: a hunt.

If it were a boar hunt with his men-at-arms as companions, Guilhem would have taken most if not all the hounds with him, but today it was just he and Henri. He whistled through his teeth, and one dog, older and shaggier than the rest, shouldered its way to the front and stood there grinning at the boys.

“There, Brusque, good old dog,” Guilhem crooned, undoing the leather hasp on the gate and letting the dog slip through. “The forest grouse are flocking, boy. We heard them yesterday while we were at lessons.”

Henri knelt and tousled the dog’s ears. A lock of dark hair fell across his eyes and he yanked it back. “And we thought, ‘Brusque needs some exercise for his fat frame.’” Indifferent to the slight, Brusque closed his eyes in delight at the boy’s touch. His tongue lolled out.

The trio left the castle by one of the arched doorways and headed across the inner courtyard for the mews, where the hunting birds were housed.

“Which falcon for you today? Which one?” Henri asked. “I will have Sharpclaw.” This was his own bird, a four-year-old peregrine he had raised from the egg.

“I will take Stripe, I think,” Guilhem said. The falcon, named for the prominent bars on his wings, would be sleeping now on his perch with the other birds. The astringer, Amis, lived in the mews as well, a wry little man who flew and trained the duke’s hunting birds. Most were short-winged hawks, like goshawks, but there were also a merlin and a couple of falcons. Stripe was Guilhem’s personal favorite. He had by now worked with the falcon for three years and felt he knew the bird well.

With the dog at their heels the boys entered the mews. The familiar scents of guano and urine-filled straw filled Guilhem’s nostrils. The birds, awakened by the footsteps, shuffled about on the long pole running the length of the enclosed room. They were tethered to it by their jesses for the night. All were hooded for sleep. Amis crept yawning out of the little room, scarcely more than a closet, at the rear where he slept. “Oh aye, young lords,” he said. “Good mornin’. What be ye after?”

“I’ll have Stripe out for a hunt this morning,” Guilhem said, smiling. He liked Amis, a gnarly man of some thirty-five summers, almost toothless but good-humored and patient with his pupils, even the impetuous Guilhem.

Presently, with Stripe still hooded but gripping with murderous talons the thick leather gauntlet protecting his wrist, Guilhem, with Henri at his side and likewise gauntleted and bearing Sharpclaw, plowed through the knee-high grass of the meadow adjacent to the keep. Broom thrust its bright yellow blossoms up among the shrubbery. To the west a crescent moon tiptoed away over the dark hills beyond the meadows. Guilhem’s heart beat with excitement. He was out on an errand of his own, with his friend, his dog and his bird, feeling most adult and proud, with his eyes wide and bright.

It was a splendid morning; cool, with mist on the ground around their feet. Walking through it felt like wading in a river of cloud-stuff. They exchanged few words in the quietude of the morning. Behind them the castle built by Guilhem’s father, Gui-Geoffroi, eighth duke of Poictiers, Comté du Poitou in this the Year of Our Lord 1083, receded into a screen of blackthorn and aubepine. It was not a large castle, housing no more than fifty people and surrounded by meadows and cultivated fields, with a marsh nearby forming a natural bulwark against incursion from the east.

Duke Gui-Geoffroi’s charge it was to oversee and protect Poitou for King Philip. Philip had annexed the verdant farmlands of the Vexin, to the north in Normandy, only the year before. According to Guilhem’s father, even though the move was wise from His Majesty’s viewpoint because of the county’s rich yields, it would provoke dissent among Philip’s already contentious vassals because of the Vexin’s proximity to Paris.

“We must be ever wary of our borders,” Gui-Geoffroi said less than a fortnight before, in consultation with his men. He’d been most forceful about it, glaring around the table with a map of the region spread out before him.

Guilhem, seated to one side but knowing enough to remain silent, always did his best to follow his father’s reasoning on such topics, and in any event had a fascination for maps. Although as his father’s heir it was his duty to understand strategy and tactics, the subjects had always intrigued him. As a child, he and Henri spent endless hours playing with a set of bronze and pewter toy soldiers, moving them about on the floor of Guilhem’s room in mock battles, carefully removing “wounded” or “dead” warriors from the field, trying to see how their lack would affect the conflict’s outcome. Soon enough now he would be commanding men in his own name: Duke Guilhem IX.

But the future held no interest for either boy this morning. Today they were simply twelve years old, out with a dog and haughty, dangerous birds of prey.

“Oh, I can’t wait any longer!” Guilhem halted in the middle of the field and removed his falcon’s hood.

“It looks to me as if Stripe would be happy enough to delay a bit, though,” Henri said, grinning. “Just a bit.”

Stripe gazed around with his sharp yellow eyes, his curved beak half open as if he were panting. He ruffled his plumage, rousing, getting ready to hunt. He was a magnificent creature, and Guilhem spared a moment to admire him, gently ruffling the soft feathers of Stripe’s breast.

“You better be careful,” Henri said. “The last time I tried that with him, he nearly took off one of my fingers.”

“Oh, he likes it,” Guilhem said softly. Stripe sat with eyes half closed now, seeming to ignore his touch.

Henri scoffed. “If you say so.”

But Guilhem understood the bird well, and knew when he could take liberties and when he couldn’t. For now, though, the boy’s thoughts were solely on his intention to bag a brace of grouse for the evening meal. “Come on, let’s go further,” he said. He walked on, with Henri at his side. They crossed the meadow at a steady pace, so as not to disturb Stripe. Sharpclaw, on Henri’s arm, was in no bad temper, and looked around, his eyes seemingly missing nothing. Brusque galumphed along beside them, grunting in pleasure and sniffing at the air. As Guilhem walked, ignoring the moisture seeping through his leather breeches, he removed the leash from Stripe’s tresses so the falcon would be ready for flight. Henri did likewise with Sharpclaw.

“Do you think we’ll see one of those young dragons people have claimed to see in the forest?” Henri asked.

“I doubt it. As long as they don’t come near the castle they don’t worry me. I can deal with small worms. Nothing over a spear’s length is anywhere around here for miles and miles, anyway, not these days; anything larger was hunted down long ago.”

“Probably true.” Everyone had seen the dragon’s head gracing the wall of the dining chamber. It was a fanged horror, as big as a washtub, killed by the duke himself some years before Guilhem’s birth.

While the boys were still a hundred or so paces from the border of the forest a pair of grouse erupted from the tall grass off to their left. One was a cock and the other a hen, Guilhem saw at once from the birds’ distinctive black markings, red wattles and the cock’s lyre-shaped tail, now appearing forked in flight. One of the birds let loose a loud, bubbling cry.

Without thinking Guilhem cried “Ho hi!” and flung his arm up to launch Stripe. At the same time Henri tossed Sharpclaw aloft. The falcons fluttered in the air for a moment as if c

onfused, then made for the much slower grouse. There was no dispute about the targets; Sharpclaw went for the female and Stripe for the male.

Then, to Guilhem’s surprise, Stripe veered off to the left, ignoring his prey. He yelled at Stripe but the hunter, oblivious to his master’s commands, dropped down into the long grass.

“Ah! Ah!” Henri cried as Sharpclaw seized the hen, wobbling to earth with it.

“Stripe, blast you!” Guilhem clenched his fists.

“He saw something else, looks like.”

“I thought he was better trained than that,” Guilhem said darkly.

The male grouse, meanwhile, fluttered to safety in the branches of a larch just inside the forest. Guilhem spat out a few words he had heard his father use and hurried with Brusque to the place where Stripe had pounced, while Henri went to Sharpclaw.

Guilhem found his falcon with its talons sunk into the neck of a stoat, not yet begun its transformation from brown to its winter coat of white. The animal was dead, and the bird glared fiercely up at the boy as he bent over it, clearly unwilling to relinquish its prey. When Brusque poked his nose closer to sniff at the stoat Stripe hissed in fury and the dog hurriedly backed off.

“Good hunting, you Stripe,” said Guilhem, but he was disappointed not to have got that grouse. He sighed. There was time for another throw or two, but any game bird nearby would probably have been scared off by now.

He extended his arm to the bird, which stared at it for a moment before reluctantly climbing aboard. “Hey ho Stripe, hey ho,” he cooed. The bird made as if to rouse again, and Guilhem smoothed its plumage, still murmuring gently. Slowly the mad light faded from Stripe’s eyes and he began grooming himself, wrapping his left wing around his head and pulling out a feather that apparently failed to meet his standards.

The Bohemian Magician

The Bohemian Magician